Follow the Science? But be wary where it leads: a new book by David Galloway & Alastair Noble

I have always been intrigued by big questions. The ‘whys?’ of life. I also admire those who are willing to explore the available facts, clarify what the data says, have the integrity to see the implications, and the determination to turn their new found knowledge into practical action. David Galloway and Alastair Noble’s new book strikes me as the epitome of that approach.

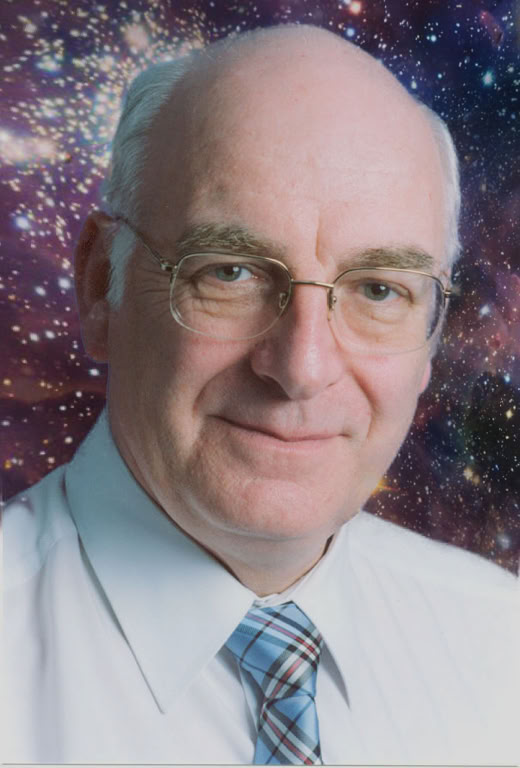

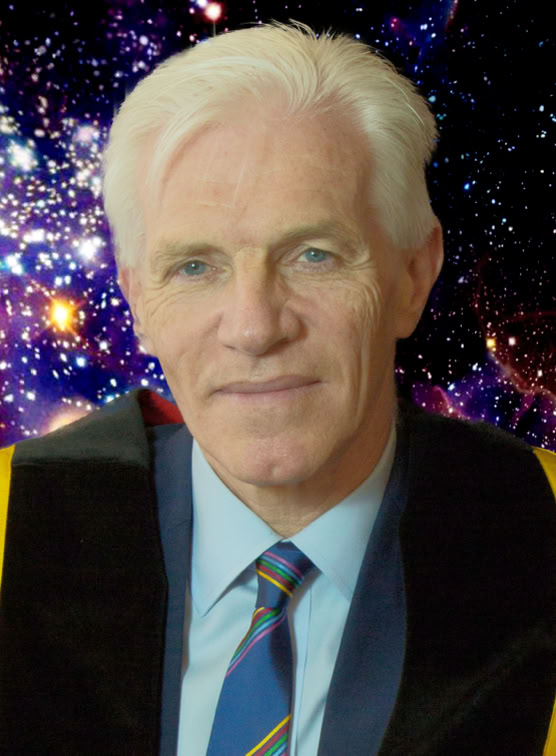

David has a medical background, as I have, and he is clearly a surgeon who is not afraid to commit his scalpel to the complex and delicate task of dissecting out ‘the limitations of science as well as its unquestionable strength’. Alastair has a background in both education and senior management and like any good educationalist has an eye to ensure that the reader understands plainly what is at stake. His practical, no nonsense, managerial style, where facts are there to be acted upon, also shines through in this book. Both authors have wide life experience, have spent decades studying the science of origins, and both have written other books as well. They are therefore well placed to tackle this topic.

The book effectively weaves together several themes. It explores what it means to ‘follow the science’, the nature of evidence, and the danger of picking and choosing our scientific facts to support a prior conclusion. In other words, the authors recognise that science is a powerful tool, but like all tools it can be used well, or abused. A number of contemporary examples of contradictory interpretation of the same facts are provided in the book to demonstrate that there is often an interpretive element to ‘science’. The limits of science when studying topics that spill out beyond the material world are also identified and considered.

The book builds on these reflections regarding scientific evidence by recognising that a mature and sophisticated assessment of all the available evidence is required to effectively ‘follow the science’. I found this a refreshing take on the topic, and an effective counterpoint to the somewhat simplistic adulation of ‘science’ or ‘scientists’ that one sometimes sees, for example, in certain parts of the mainstream media.

The central theme of the book concerns the application of the lens of ‘science’ to some of life’s big questions such as:

• Where did the universe come from?

• How did life begin and develop into the biodiversity around us?

• What is the origin of mind and consciousness? (p28).

A book of 150 pages can only cover the breadth of that landscape to a limited depth, but the authors do an excellent job of providing a summary that is neither simplistic, nor beyond the grasp of any interested reader. There are relatively short and easily comprehensible chapters on ‘The Science of Origins’, ‘The Origin of Life’, and a longer chapter on ‘Detecting Design’. The latter ends by exploring the evidence that mind, consciousness, morality, and conscience point to a transcendent origin of these key facets of our existence, that is, they provide evidence of a realm beyond the purely material.

The final section of the book draws out the authors’ personal journey of ‘following the science’ and integrating it into a ‘world view’ that incorporates evidence from a wide range of domains that complement and enhance their understanding of science and result in a comprehensive and integrated whole. This is a tricky task. It involves recognising that although there is large agreement on the ‘facts’, there is disagreement on the interpretation of those facts.

Design in nature is controversial. Whether you agree with it or not, this is an excellent introduction to key concepts which challenge a materialist worldview. Enjoy the debate!